HISTORY

OVERVIEW

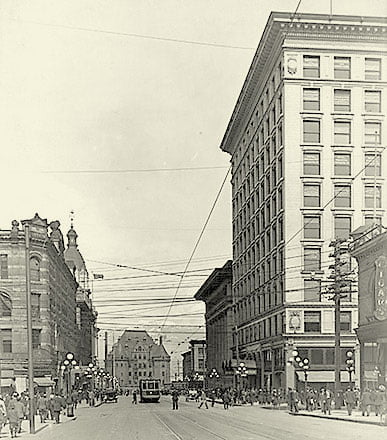

During its construction, The BC Saturday Sunset reported:

“The building will be a monument to Alderman Rogers, whose faith in the future of this city is exemplified in the erection of a building which, when completed, will represent an expenditure of nearly $600,000.”

PERSONALITIES

Jonathan and Elisabeth Rogers

Jonathan Rogers was born at Plas-Onn in Denbighshire, North Wales, and moved to Liverpool at age 16, learning English while working various jobs. In 1887, he sailed for Montreal and crossed Canada on the first transcontinental train to Vancouver. The first passenger to emerge from the train, he was greeted by the Vancouver City Band striking up See, the Conquering Hero Comes!, later admitting (with embarrassment) that he thought the band was playing it for him as the first person to disembark.

Rogers attended the first public CPR land auction and purchased four lots in what is now the West End with money inherited from an aunt, later parlaying it into his fortune. At first opening a tool and paint shop, he became a successful contractor and developer, eventually building an estimated 1,000 feet of commercial frontage. Prominent among these properties were the St. Francis Hotel, Buntzen Lake Powerhouse and four buildings for the Royal Bank, as well as the landmark building at 470 Granville Street which bears his name.

Deeply involved in public life, Rogers served two years on City Council, 26 years as a Park Board commissioner and two terms as president of the Board of Trade. In 1911, when the Rogers Building was under development, he was one of the twelve charter members who founded the Building Owners and Managers Association of British Columbia (BOMA BC), an organization which continues to this day. He was a lead proponent in BC’s Prohibition movement.

His wife Elisabeth, whom he married in England in 1902, had travelled extensively in Europe and been presented at court to Queen Victoria; she was an erudite and cultured partner. Together the couple was among the founders of the Vancouver Art Gallery – conceived at a meeting in their parlour – as well as the Symphony Society, which would later become the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra.

Jonathan died in Vancouver on December 8, 1945 and was buried in Mountain View Cemetery. He left $250,000 towards a number of causes, including $100,000 for the provision of a park in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood. Occupying a full block, Jonathan Rogers Park was dedicated in his name in 1958. Elisabeth Rogers Community Garden located within the park was named in his wife’s honour in the 1990s.

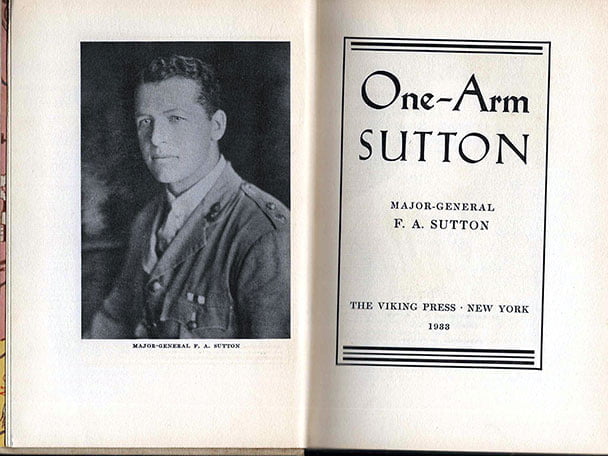

Major General “One-Arm” Sutton

The building’s second owner, Major General Francis Arthur Sutton M.C., who owned the building between 1927 and 1940, was an English adventurer whose exploits were famous. His nickname “One-Arm” was obtained after losing part of his right arm after being hit by a hand grenade at the Battle of Gallipoli.

An engineer by training and in early search of adventure, Sutton was in Paraguay building a rail line through uninhabited swamps and forests before the age of twenty. He learned to speak Spanish, and after being married in England in 1909, travelled to Mexico to work in Lord Cowray’s oil refineries. Here he contracted malaria and slowly worked his way north along the Mississippi. He stayed in Michigan long enough to find a job shovelling concrete and finally saved enough to return home.

When war broke out in Europe, Sutton had been building bridges in Argentina, but quickly returned to join the war effort. Given his education and experience, he was commissioned to the Royal Engineers. A lieutenant with a detachment of 30 men, as well as a golf enthusiast, he landed in Alexandria to join the Gallipoli expedition with his golf clubs labelled as equipment – only to be exposed when a piece of shrapnel tore open his bag. Under attack, he was catching enemy hand grenades and tossing them back, when one misfired, taking his hand. Thrown backwards, he was pounced on and managed to kill his attacker in hand-to-hand combat, despite his mangled arm; for this, he was awarded the Military Cross and promoted to captain.

Following his convalescence, he was assigned to the Army’s Inventions Department of the Ministry of Munitions, where he invented several improvements to trench mortars, and went so far as to test them himself in the Flanders battlefield. He was eventually assigned to the United States when they entered the war, and where he supervised mortar production for the American government.

Amid stories of the Russian Revolution, Sutton heard about the opportunity for gold in Siberia. He wasted no time and bought a 300-lb. gold sledge which he transported across the Pacific to Kobe, Japan, and made a perilous journey through Vladivostok, eventually reaching Blagovyeschchensk before heading further north to the Zeya River. Along with his sledge, he arrived with a cargo of thousands of tons of merchandise (including 10,000 pairs of shoes, 700 tons of nails and 50 tons of horseshoes!) purchased with his entire savings. Here, he made and lost a fortune in gold (reportedly $1 million), and courting danger between warring factions and government officials, escaped to Shanghai with $200,000 which he promptly lost in their stock market.

Now bankrupt and in China, he turned his earlier work to his advantage and built a production line to manufacture the Stokes Mortar, which he sold to various warlords at great personal risk. He was made a major general and advisor for the Chinese warlord Chang Tso-Lin (aka Zhang Zuolin) after the success of a major battle that captured the Great Wall. Chang ultimately conquered half of China with Sutton at his side. Having again made a considerable fortune, Sutton moved to Shanghai, where he even bought a racehorse – Bengal the Wonder Pony – which would win 41 of his 42 races, including the highly lucrative Champions Sweepstake. In 1927, Sutton left for Canada.

Sutton arrived in Vancouver with the £500,000 he had made gun-running and the idea that he would open up the Peace River region by building a railway to link Vancouver with Edmonton. It was during this time that he purchased the Rogers Building – a transaction of $1.2 million that made the papers as the city’s largest real estate transaction to date. Lesser known was his reason for purchasing the building – he was a tenant and annoyed that the building’s manager had refused to make structural alterations to his suite of offices.

He also purchased his residence at 1495 Balfour, as well as Portland Island, where he hoped to raise and train thoroughbred horses, as well as build a luxury resort, complete with golf course and “the best pheasant shooting in the British Empire.” It was said he enjoyed many champagne-fuelled parties on yachts during his time there and that he made a “famous 1000-yard swim when he jumped from the Victoria boat which was passing his Portland Island home.” For this escapade, he was charged and fined on behalf of the Canadian Pacific Railway for delaying the boat which had to be stopped for a man overboard.

While attracting much publicity, Sutton’s scheme for a railroad failed to materialize when he couldn’t attract investors and his fortune was lost in the 1929 stock market crash. “Chinese wars seemed simpler,” he said. (A railway linking Vancouver with Edmonton was later built in 1958.)

Undeterred, Sutton travelled to Alberta to work on opening up Peace River country, but the call for adventure soon returned and he returned to China in 1932 with a shipload of mass-produced metal coffins to sell. It was reported that he was also working (or under the guise of working) as a war correspondent for the London Daily Express during the Japanese seizure of Manchuria and Jehol.

While all of this was occurring, foreclosure on Portland Island was imminent and Vancouver papers were reporting that the Supreme Court of British Columbia had given Roy Manzer, a lawyer representing Clovelly Limited, a deadline of two months to track him down in China and serve him foreclosure notice.

“Mr. Manzer told the justice today that General Sutton had not paid his mortgage interest on the island for more than eighteen months and is some place where he can’t be found in the far interior of China in parts entered by no other white man. ‘General Sutton has been a famous soldier of fortune in Siberia and China,’ Mr. Manzer said in his statement to the court. ‘In his recent book he relates some of his experiences and indicates that between 1922 and 1927 he was serving in a military capacity under Marshal Chang Tso-Lin and that during part of that time he was chief advisor to the Chinese lord.’ Now that the leave to proceed against him has been granted, Mr. Manzer said, he would have to work out a method of serving the elusive soldier of fortune in some isolated part of China.”

– The Daily Province, October 10, 1933

The island was seized by the court the following year for the $15,835 mortgage judgement. It was explained that Sutton had failed to appear, as “the General was last heard of in Harbin, where he had again gained a position of power with Oriental war lords.”

In 1933, he set off for Korea, where he believed gold deposits comparable to those of Siberia could be found. He mined here until 1938, before being arrested and deported to Hong Kong by the Japanese who believed he was heading a British spy ring. He was still residing and doing business there when they attacked in December 1941. Once again in the fray, he was captured and tortured for information about Chinese troop movements and ammunition dumps, and reportedly refused to talk. Sutton died of dysentery in 1944, still interred at the Stanley Interment Camp and is buried in the camp’s cemetery. The second part of his memoirs had already been drafted and was last seen in his offices in 1941; the manuscript that was to begin with his adventures in China has never been recovered.

In 1938, Mrs. Elisabeth Rogers had foreclosed on the Rogers Building for non-payment of a second mortgage in excess of $600,000 and the namesake skyscraper was sold back to Jonathan Rogers in 1940.

TENANTS

“It is only necessary to glance at the list of tenants to see that the painstaking efforts of Mr. Rogers are thoroughly appreciated by the most enterprising citizens of this most enterprising city.”

– The Daily Province, 1913

Jonathan Rogers designed and maintained his namesake building with his commercial tenants in mind, providing free janitorial service to their offices with a team of twenty janitors and offering electricity at a reduced rate. Chief janitor Mr. Dickie was interviewed in 1913:

Notable tenants over the years have included the Chinese Consulate and O.B. Allan Jewellers, which occupied the southeast corner storefront from the building’s opening in 1912 until the 1980s.

In 1995, that storefront was replaced by Dunn’s Tailors, whose memorable art deco neon sign required a heritage designation to obtain city permission to relocate from its original location on Hastings Street, where it had been since 1946. It was removed when Dunn’s vacated that location in 2020. When the building first opened, the newspapers were thrilled with Sorensen’s Cafeteria:

“Sorensen’s Cafeteria, Rogers Building, open to the public at 11 a.m., Saturday. Lunch in the cleanest and most elaborate cafeteria on the Coast.”

Foremost heritage expert and author Donald Luxton has been a long-term tenant of the building, and Vancouver historian and author Chuck Davis maintained an office in the 1990s.

TIMELINE

- 1911 • May 30: building permit issued.

- 1911 • June 1: construction begins.

- 1912 • February 19: structural work completed; year of completion.

- 1927 • September 2: sold to One-Arm Sutton for over $1 million – Vancouver’s largest real estate transaction at that time.

- 1938 • Mrs. Elisabeth Rogers forecloses on the Rogers Building for a second mortgage owed by General Sutton.

- 1940 • The building is sold back to Jonathan Rogers.

- 1955 • The building is sold to the Koerner Foundation for $1.25 million.

- 1976 • The building is sold to Equitable Real Estate Investment Corp. for $2.25 million; addition of external fire escape.

- 1986 • Recognized as Type A Heritage building by City of Vancouver.

- 2003 • City of Vancouver Heritage Award of Merit for restoration of the exterior lobby and part of the retail storefront.

Top photo: Martin Knowles Photo Media; others: public domain.