ARCHITECTURE

HIGHLIGHTS

Prominent land developer Jonathan Rogers chose the Seattle architecture firm of Gould & Champney to design his namesake building in the Edwardian Commercial style in 1911. Red granite is used for the monumental ground floor columns, with cream-coloured glazed terracotta for the upper floors, crowned by an ornamental galvanized steel cornice.

In his Parks Canada manuscript Vancouver Architecture, 1896-1914, Edward Mills described the building’s design as being “of the modern French Renaissance” and compared it to architect Gould’s earlier American Bank and Empire Building in Seattle:

“Both buildings possess elaborate ground floor bases, elegant but light classical cornices and a somewhat plainer, flat series of storey in the intermediate stage. Any French Beaux Arts influences are no doubt attributable to the training in Paris of both Gould and Champney. While Gould placed plain Doric columns in his Seattle bank entranceway, the Rogers Building in Vancouver boasts a pair of grand pink granite Ionic columns; similar pilasters of the same material are placed to define additional ground floor bays.

“The structure is built about a steel skeleton frame with poured concrete infill. Outside facings are in cream-coloured terracotta while interior hallways possess much of their original white Italian marble and dark hardwood veneers. Two separated stairways of marble with polished brass handrailings still survive, and lead from Granville Street to businesses underneath the building.”

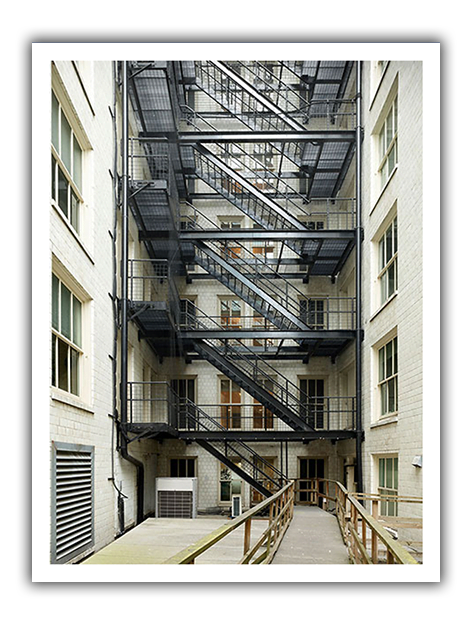

Not visible from the street, the building’s rear façade reveals its U-shaped design which facilitated the reach of natural light to its innermost offices.

ARCHITECTS and BUILDERS

Augustus Warren Gould and Edouard Frère Champney’s partnership lasted for three years (between 1909 and 1912), and the Rogers Building was one of only two designs the pair produced for development in Vancouver.

Augustus Warren Gould (1871-1922)

Born in Nova Scotia, Gould practised in Boston, Seattle and Vancouver, worked in Seattle on buildings such as the American Savings Bank and Empire Building (1906), which were the second and third concrete-reinforced structures in the United States, as well as the King County Courthouse. Perhaps surprisingly, Gould was not formally trained as an architect, but rather had a background in building and contracting. As Sean Rossiter describes him in The Greater Vancouver Book:

“When the worldwide collapse of lumber prices in 1910 ended Seattle’s boom, Gould and other architects travelled the short distance north to Vancouver where higher prices persisted because of B.C.’s access to British markets. Gould’s Rogers Building (1911-1912) at 470 Granville is one sumptuous example of what architects from a more sophisticated city could do in booming Vancouver.”

Edouard Frère Champney (1874-1929)

With degrees from Harvard and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Champney began his career with Carrère and Hastings in Buffalo, who were the principal designers for the Pan American Exposition of 1901. He would become assistant chief architect for the Louisiana Purchase St. Louis Exposition, worked on the master planning for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland and became the chief architect for the 1909 Alaskan Yukon Pacific Exposition. In 1912, he was appointed the chief architect of the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

Albert Gardener Wood (1886-1973)

Born in New York, Wood moved with his family to Seattle as a teenager and was working as an architect by 1910. He moved to Vancouver to manage the local Gould and Champney office and was the supervising architect for the Rogers Building. He married his wife Louise in Vancouver in 1912 – the same year he formed a brief partnership with A.W. Gould, maintaining an office in the completed Rogers Building. Their partnership was short-lived and Wood moved to Detroit in 1917, where he became the head architect for the construction of Henry Ford Hospital.

The Purdy and Henderson Company Limited

Lightner Henderson obtained his B.S. in Civil Engineering from Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, in 1889 and was a member of Western Society of Engineers (1891-1916). He was a writer and often spoke at national events for professional groups, as well as gave keynote speeches and educational lectures at engineering schools, including his alma mater and Cornell University.

Corydon Tyler Purdy had been a draughtsman and surveyor’s assistant in Milwaukee, Saint Paul and Chicago, IL, in the early 1880s, specializing in bridge design – a skill he later applied to skyscrapers. He was a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers; Institute of Civil Engineers of Great Britain; the Western Society of Engineers; and the Engineers’ Club of New York, among others. He won the Telford Premium Medal, Institute of Civil Engineers, London, in 1909.

CONSTRUCTION

“An absolutely magnificent example of the builders’ skill, and a triumph of sanitary, hygienic and technical engineering is the Rogers Building at the corner of Pender and Granville streets. Owned by Mr. Jonathan Rogers, managed by Mr. George W. Melhuish, this ornate structure represents all that is latest and best in the world of building and allied trades. No expense has been spared, and the foremost centres of building have been searched to obtain all that is latest and best for office building purposes, and the result is a triumph of architectural design, of building art and engineering science, and a tribute to the enterprise of the owner, Mr. Jonathan Rogers.”

– The Daily Province, 1913

The building permit for the Glyn Building – its originally announced name – was issued on May 31, 1911 with a listed value of $550,000. The New York-based engineering firm Purdy and Henderson Company Limited, which had offices across the United States, was hired as engineer and contractor. The building’s construction was a going concern. As reported in The Engineering and Contract Record:

“The architect, A. Warren Gould, of the firm of Gould & Champney, and the owner, Jonathan Rogers, are at present visiting Chicago, New York and Toronto, their object being to interview the various manufacturing plants and dealers in high-class finish. The trip will probably include a visit to England, as it is possible they may purchase the terra cotta and special plumbing fixtures abroad.”

The chosen finishes would include fifteen carloads of enamelled terracotta from Chicago; ornamental iron from Minneapolis and St. Paul; five of the most modern elevators from Toronto; solid bronze entrance doors costing $2,500; and 8,000 barrels of cement from California; 60,000 feet each of cork flooring and “Battleship” linoleum from England were used in the construction of the building. Innovative for its time, the cork was glued to the cement floors, and the high-traffic linoleum, named for its original use on US Navy warships, installed on top of it.

The Daily Province described the building’s attributes in 1913: “At the corner of Pender Street West and Granville Street the Rogers Building is the latest ideas of reinforced concrete construction and the first ten-storey of its kind in Canada. The basement excavation is 20 feet, the height almost 120 feet and occupies 120 feet on Granville Street and 104 feet on Pender Street. Marble from Alaska is featured in the halls, and from Vermont and Tennessee for the main entrance.”

The Record also reported that a wing of the building would “be fitted up for doctors and dentists, for whose convenience special electrical and compressed air appliances will be introduced.”

With close to 342 office spaces, the building was designed in a horseshoe configuration with a 24-foot light well at its centre so that there was “not a dark room in the whole building.”

The elevators were built by the Otis-Fensom Company of Toronto and equipped with the latest safety features, including guides which could prevent a car from going too far up or down, and governors which could act as an emergency brake to automatically halt the car if its speed became too great. The “can’t fall” elevators were suspended from six cables (as opposed to the usual four) and included Norton door closers specially designed to prevent accidents. The cars each had the capacity to lift 2,000 lbs. at a rate of 400 feet per minute with one further equipped with a compound gear that could be coupled to increase the car’s capacity to two-and-a-half tons. A new “flash-light indicator” system used coloured lights to display the direction elevators were travelling. A starter (originally Mr. H.E. Baker) with six assistants was responsible for dispatching the elevators, of which one was kept operational twenty-four hours a day.

An innovative ventilation system purified the air by passing it through a sheet of falling water, cooling it in summer and then heating it with a steam jet in winter. A large fan blew this air up a long shaft that reached from the engine room at the rear basement all the way to the roof, where a second fan expelled the bad air. It was said that the basement’s air was fresher than that on the sidewalk.

Two 150-horsepower Babcock & Wilcox high-pressure boilers produced and maintained the building’s steam at 160 pounds to the square inch – far more than would be required to heat the offices, as Rogers wanted to ensure there was sufficient steam on hand for lighting should the electricity fail. The boilers were fuelled by oil:

“The boilers are heated by oil fuel, and so great is the heat given out by the oil that it is possible in ten minutes from the time of lighting to bring the huge boilers from zero to the full pressure of 125 pounds to the square inch. The glare of the burning oil which is drawn into the fuel chamber by steam, after the first ignition, which is performed by compressed air, is, when at its fiercest, pale blue with a heart of blinding white, and is a great sight to witness.

“Mr D.H. Judd, the chief engineer in charge, who keeps all the plant with the aid of two assistants, stated that there was only one fuel to use, and that was oil. It was far more economical and cleaner than coal, and did much better work in less time. The oil was pumped into the jet by a pump, to which was attached an oil meter, whereby the consumption could be gauged.”

Conscious of the changing workforce, the building even included a women’s restroom with an attendant and a gas stove to make tea.

HERITAGE PRESERVATION

Colour photography: Martin Knowles Photo Media. Others: public domain.